Identifying Compromises Through Device Profiling

The Internet and our local networks have the ability to handle an amazing quantity of connections simultaneously. That strength leads to a problem when we’re trying to detect malicious traffic: how can we tell when one of our systems is sending traffic that it shouldn’t? In this article, I’ll show you how to detect these malicious patterns by combining two open-source software packages.

Identifying Compromises Through Device Profiling

Attackers depend on us not seeing everything that goes on on a network. A single network device, once hacked, can be used as a gateway for attacking other systems. It can be an exfiltration point for your internal documents, or a jump point to sabotage vital industrial control systems.

A few years ago my wife and I traveled to Japan. While we were there we saw Shibuya Crossing, one of the busiest intersections in the world: See Here

Having worked in network and Internet security for years, this intersection reminds me of the reality of trying to detect malicious traffic:

- The amount of traffic flowing right by us is immense.

- That flow includes legitimate traffic, malicious traffic, and background noise.

- Even if we had a live human watching that flow 24 hours a day, we’d still not be able to identify the malicious traffic.

- The job of any security tool is to allow us to “see” all this traffic by collating, categorizing, and summarizing it for us.

Let’s say your job was to identify money mules (people withdrawing money to give to criminal enterprises) crossing that intersection. How would you do it? I’d start by looking at the buildings around that intersection and identifying which of them contain banks or money order services. By performing facial recognition on the people coming out of those buildings I could track who went in or out of those far more commonly than normal – they would be my initial group for further investigation.

On a network, we can leverage similar techniques. We can identify devices that send large amounts of traffic in or out of the network and follow up with each to see why. Let’s step back for a few minutes and think about the systems on your network. While it’s true that you have a mix of devices, there’s probably some homogeneity in the hardware and operating systems you have. The first step is to group your devices together by hardware type: routers, industrial control units, cameras, temperature sensors, laptops, etc.

Once you have a group of relatively similar network devices, now you can consider what kinds of traffic those machines should have. The cameras send video clips at regular intervals to a central server. The industrial control units send out status reports and expect the occasional command from a central server. Windows and Macs are a little harder to profile because they generate so many types of traffic, but with a little work, it’s possible to profile them too.

Let’s say we could come up with profiles for our different categories of devices, such as “on a given day, a camera generates between 10 megabytes and 200 megabytes of HTTPS (encrypted web) traffic”. Is there a way to give us an alert if one of those cameras sends too little traffic (powered off, perhaps?) or traffic to a new external system (device may be controlled by an outside attacker).

Normally this would be a major undertaking, with lots of hardware to purchase, an expensive piece of software, and a support contract that chews through our IT budget all too quickly. In this case, we can use a piece of software you may already be running, another free software program, and some setup time.

Many shops already run the Zeek network monitoring package to help identify traffic going in and out of the network. Zeek has a healthy ecosystem of addons that can look for suspicious patterns. In this case, we want to identify whether a system is sending too much data, too little data, or even just unexpected data types. We’ll make use of devprof, a free tool from Active Countermeasures, to look for the amount of each type of data generated by a system over a 24 hour period.

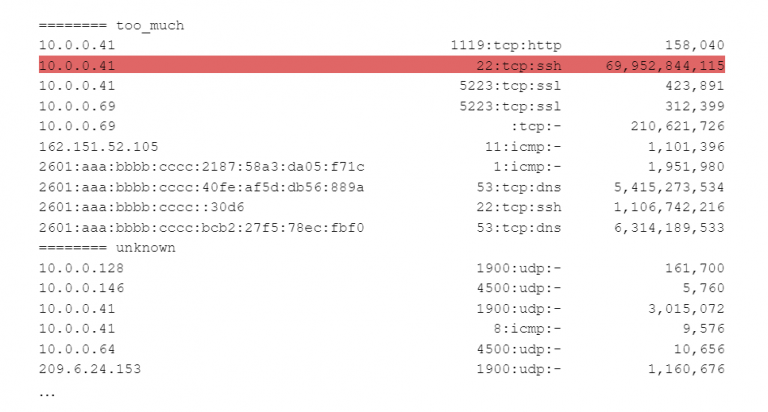

To set it up, we take a number of similar devices on the network, jot down their IP addresses, and then enter a list of the types of traffic they should be generating and the minimum and maximum amount of traffic for each. Next, we run devprof, handing it the profiles we created and the Zeek logs for the previous 24 hours. devprof’s job is the hand us back the systems that are generating traffic outside those limits. Here’s an example:

In the red highlighted line above, the machine at 10.0.0.41 has sent and received almost 70 gigabytes of traffic in a day. The profile we worked from said that machines in this group should transfer no more than 10GB of data per day – so we would want to investigate why this system is sending so much traffic. More about The Importance of Security by Design for IoT Devices

Unlike a tool that requires you take on the whole network at once and understand all the traffic patterns right off the bat, devprof allows you to consider just a small number of machines at a time, working your way through the most critical and least-watched devices first and expanding outwards. We can always adjust the traffic ranges in our profiles when benign traffic shows up in the report and add new traffic types over time.

References

This article was written by Bill Stearns. Bill provides Customer Support, Development, and Training for Active Countermeasures and originally it was published here. Bill has authored numerous articles and tools for client use. He also serves as a content author and faculty member at the SANS Institute, teaching the Linux System Administration, Perimeter Protection, Securing Linux and Unix, and Intrusion Detection tracks. Bill’s background is in network and operating system security; he was the chief architect of one commercial and two open source firewalls and is an active contributor to multiple projects in the Linux development effort.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Pingback: Identifying Compromises Through Device Profiling – IoT – Internet of Things