Building Trust in the Smart City – Think Beyond Cybersecurity and Privacy

What is trust in the smart city and why is it important?

Smart city projects represent one of the hottest initiatives among city leaders, urban planners and technology vendors today. According to IDC, these initiatives will translate to $80 billion of technology investments worldwide by 2018 and $135 billion by 2021. While the smart city may be powered by technology and data, it is really enabled and sustained by the trust its stakeholders have in it.

A smart city works when there is an implicit trust in the relationship its stakeholders have with the city, its services and its service providers. When there is no trust or that trust is lost, its stakeholders will not come back and use its services. Even worse, they will withhold participation, and stop providing critical information. When that happens, the smart city declines in value. Its services will be underutilized as people seek alternatives. Smart city services become irrelevant as expected outcomes do not materialize because they lack the critical input and support from the stakeholders it was intended to serve.

In order to be relevant and remain so, a well functioning and sustainable smart city must design trust in right from the beginning. This trust must be integrated into all aspects of the smart city – its people, processes, management, policies and technology.

Air Transportation: An example of trust in action

The air transportation industry is built upon “trust”. Very few people will willingly fly in a plane if it wasn’t safe, nor will they use it to ship packages if it won’t “absolutely positively” get there safely and on time.

Fortunately, air transport is safe and reliable. According to the June 2018 International Air Transport Association (IATA) industry statistics, air carriers reported 4.1 billion passenger miles flown and 61.5 million freight tonnes shipped globally. The United States Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) manages an average of 42,000 flights carrying 2.6 millions passengers in its airspace alone in 2016. Despite this volume, air transport is relatively safe. The IATA reported 45 accidents in 2017, down from 67 in 2016 and a high of 86 in 2013. Accident rates, per million miles, was 1.08 in 2017, down by half over the previous 4 year average of 2.01.

An air transport “trust ecosystem” ensures that flying is safe and reliable. A combination of rigorous engineering, regulations, policy, operational processes, stringent oversight and maintenance have made air transport remarkably safe. An ecosystem of partners, from government agencies, aircraft and component manufacturers, airlines, engineers, and others have worked together to ensure these outcomes.

Trust in the Smart City: More than cybersecurity and privacy

Mention trust in any smart city conversation, and it quickly turns into a privacy and cybersecurity discussion. While important and relevant, they are only two elements of many that create trust in tomorrow’s smart cities. Distilling the concept of trust (and ultimately the solution) into these two elements oversimplifies the challenges involved and misses important underlying contributing factors. This results in inadequate approaches and solutions in creating trusted smart cities.

While smart city planners speak in terms of trust, residents and businesses are concerned with outcomes. When a city creates services that provide the outcomes residents and others expect and rely on, then the sense of trust is earned and reinforced. Residents expect that the bus service gets them to work and back home safely and on time everyday. They expect police and emergency services will arrive quickly regardless of whether they live in a rich or poor neighborhood. They expect that red light cameras are used to catch traffic violators, and not to track their movements around the city.

Trust Defined

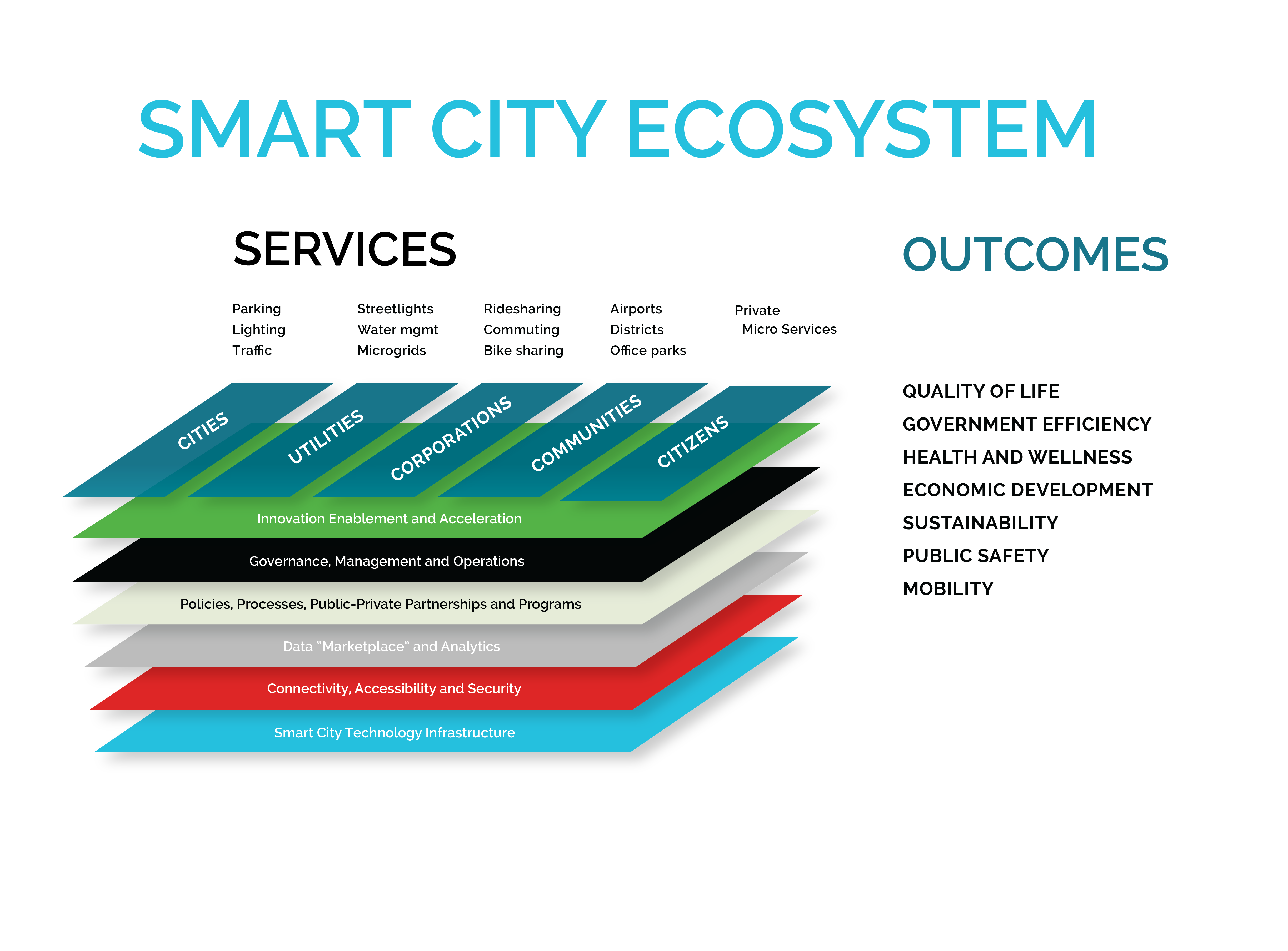

We describe trust in any city, smart or not, as the firm belief in the outcomes of the services provided. These services may be provided by the city or others in the smart city ecosystems (Figure One). These outcomes are trusted when they are relevant, rendered reliably and with integrity, by service providers who are credible, transparent and have the capacity to execute.

Trust begins when a smart city consistently develops services and outcomes that are relevant when it is appropriate and of value to its users. Any city or service provider that fails to do this risks being called out for misusing taxpayer money and resources.

Services and outcomes must be rendered reliably and with integrity. No one would use a service if its outcomes cannot be delivered reliably and consistently. No one would use ridesharing if they cannot find a ride and get to their destination on time safely. Equally important, services must be rendered to deliver the right outcomes they were designed for. They must be rendered accurately, legally and in compliance with regulations or policies, and for its intended use and not any other use.

Service providers must be credible, transparent, and be able to deliver the desired outcomes. They must be knowledgeable and experienced in their field, trained, and if appropriate, certified. When rendering services and creating outcomes, they must be transparent, fair and unbiased, collaborative and adaptive when necessary. Finally, they must have the capacity and capability to execute and deliver the services and outcomes.

Ten Levers of Trust Enablement

In order to create trusted outcomes, planners and services providers have several “levers” that they can use. The careful selection, coordination and application of these levers will help build trust in new services, or to increase trust in existing deployed services. The levers include:

- People and Organization – skills, expertise and certifications; jobs, roles and responsibilities; teams and organizational structures for execution

- Change and transformation management – engagement of affected stakeholders before, during and after. Includes communications, training and cultural management.

- Governance – management, policies, legislation, audits, oversight, documentation, traceability, and metrics

- Processes – control and determine how the service is developed and rendered

- Data – information used to build the service, as well as information created as a result of the service. Data must be representative and unbiased. Data must be protected and private.

- Algorithms – machine learning and other algorithms that define the service, as well as how it is delivered to its users

- Technology – tools for developing and operating the service, as well as connectivity, infrastructure and solutions for delivery of the service

- Security – safety, privacy and protection of assets, tools, infrastructure and users

- User Experience – how service providers and users interact with the service and its outcomes

- Strategic – vision, planning, partnerships, funding and resources

The ability of the city and its service providers to strategically develop and deploy these levers is a core competency and a critical success factor in building a smarter and more responsive city. Over time, as the service matures, and as users expectations and needs change, these levers must be continuously examined and adjusted to maintain or exceed current levels of trust.

Putting it all together: The Smart City Trust Framework

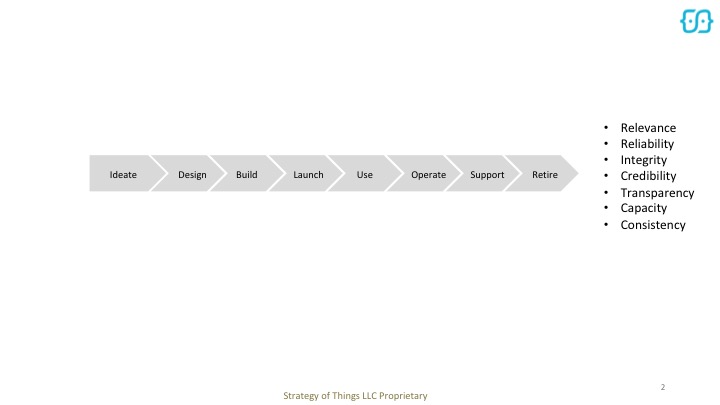

Trust doesn’t magically happen by itself in a smart city. It must be carefully embedded and orchestrated across the entire smart city ecosystem (Figure One). It must be incorporated into the processes and programs that create smart city services throughout its lifecycle, from design, to development, launch, operation, delivery and use to ensure “trusted outcomes” (Figure Two). Equally important, building trust is not the sole responsibility of the city itself, but everyone who “touches” the smart city – from beneficiaries, service providers to planners and policymakers.

We propose a framework for building trust into the smart city (Figure Three). Trust is created when services from the various value creators (cities, utilities, communities, corporations and individuals) in the smart city ecosystem (Figure One) create outcomes that are relevant, rendered reliably and with integrity, by service providers who are credible, transparent and have the capacity to execute.

However, the elements of trust must be considered and incorporated at each phase of the services lifecycle. This is done by examining the various levers of trust, and incorporating the appropriate specific tactics at each lifecycle stage, in order to create the proper outcomes. There is no one size fits all set of tactics. While there may be some common tactics, they will vary from service to service, provider to provider and city to city.

Take the example of a city that wishes to deploy smart and connected city lights. This new service allows the city to remotely monitor and manage its streetlights. If a light is not functioning properly, they will know immediately and schedule a repair. The connected lighting system also incorporates machine learning algorithms which will proactively alert the city of impending failures so that it can be serviced before an actual failure can occur.

Upon the deployment of this smart lighting service, business as usual is not good enough. Trust in this service and the public works department (and ultimately the city) is diminished when the lights are not repaired quickly because there is now no excuse for not knowing a streetlight is out. Trust in the service is diminished by the Public Works team if the technology indicates that the lights are functional when it is not, or if the light needs servicing when it does not.

Resident and other stakeholders must be engaged to understand their needs and expectations. Current processes, performance metrics, policies and systems must be redesigned to allow the city to respond to outages in days, not weeks. In addition, changes to the organization, including jobs, roles and responsibilities, team structure, culture and accountability reporting will be necessary. To minimize the disruption caused by these changes and facilitate adoption by both city employees and residents, change and transformation management activities, including communications and training, must be conducted prior to the actual service changeover.

The new service is only as effective as the technology, algorithms and data enabling it. Machine learning algorithms must interpret the sensor data from the remote streetlight controller units and distinguish between a true anomaly and a false positive. In addition, these algorithms must predict with high accuracy when the lights may need servicing by examining the sensor data. To maintain this accuracy, these algorithms must be continuously trained by certified experts using representative and unbiased data sets. Finally, the connected streetlight system must be secure, and not allow for unauthorized access to the lights, nor disrupt the metering and billing systems.

What should smart city architects and planners do now?

Trust is critical part of a sustainable and well functioning city. Whether building an entire smart city or a specific smart city service, a “trust ecosystem” must be built in right from the beginning as part of the larger smart city ecosystem. Trust is much more than security and privacy, but a complex set of enablers working in unison over the entire smart city services lifecycle to deliver the outcome that its stakeholders expect.

Regardless of where cities are in their journey, smart city and service planners must get ahead of the “trust curve”, and take steps to build out this trust ecosystem. Key next steps are:

- Understand the trust ecosystem framework and adapt it to the realities of your specific city. The framework shown here is a template for reference purposes. Not everything will apply, and it may not call out everything you need. Adapt and build upon it to suit your specific vision, strategy and execution plans.

- Understand the current state of your trust capabilities and trust ecosystem. Conduct a high level “trust diagnostic” using the framework to quickly identify areas of strengths and weaknesses. Build a trust development plan.

- Evaluate ongoing and planned smart city services and projects against the framework. Use this framework to identify what is missing from the project plans and what is needed to make the projects more “trustworthy”.

- Build your “trust capabilities” by identifying and focusing on high priority areas. Build your capability through a combination of internal development, outsourcing, augmentation and strategic partnerships.

![]() This article was written by Benson Chan, a Senior Partner at Strategy of Things, a transformation management consultancy helping companies innovate for a hyperconnected world. He has over 25 years of scaling innovative businesses and bringing innovations to market for Fortune 500 and start-up companies.

This article was written by Benson Chan, a Senior Partner at Strategy of Things, a transformation management consultancy helping companies innovate for a hyperconnected world. He has over 25 years of scaling innovative businesses and bringing innovations to market for Fortune 500 and start-up companies.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Pingback: Building Trust in the Smart City – Think Beyond Cybersecurity and Privacy | iotosphere - Internet of Things