An Executive Order (EO) issued by a U.S. President is usually a pretty straightforward document. Most are just two or three pages long with a handful of directives. This is definitely not the case with President Biden’s latest EO, Executive Order on Improving the Nation’s Cybersecurity. This is a massive policy document weighing in at 15 pages with 74 actionable directives. Forty-five of those directives have defined due dates, many of which are linked to the completion of other directives. Add to all of this a boatload of acronyms and abbreviations specific to the cybersecurity industry and the result is a document that could take months to fully decipher.

Who Does this Executive Order 14028 Affect?

With Cybersecurity in the title, you know the EO is going to impact companies that supply IT products and services to the U.S. Government. However, this new order is more than a list of IT regulations. The EO’s writers repeatedly call out Operational Technology (OT) in both the introduction to the EO and the accompanying EO FACT Sheet. It then switches focus to a more general term, Critical Software, as it spells out the list of requirements and directives that will be mandatory for all software sold to the U.S. Government.

So what exactly do they mean by Critical Software? Right now, we can’t be sure. However, after the recent Colonial Pipeline incident, it’s probably safe to assume that OT software is included in this category. A definitive answer on this isn’t far off though: the Director of CISA is tasked with providing a list of software categories meeting the definition of Critical Software by July 26.

Of course, the companies affected by this order don’t have months to understand how it will impact them. They need to figure this out now so that they can implement a plan to meet the new requirements. This is especially true for companies that supply the aforementioned Critical Software to the U.S. Government.

With so much information to absorb, I thought it would be helpful to provide a quick summary of what I believe are the key takeaways in Executive Order 14028.

Cybersecurity for the Software Supply Chain

I’ll start with the observation that securing the software supply chain is arguably the major focus of this EO. Almost 1/3 of the document’s policy statements are in Section 4: Enhancing Software Supply Chain Security. This is no surprise after the SolarWinds attack in December infiltrated all five branches of the U.S. Military, the Pentagon, the State Department, the National Security Agency, the White House, and a whole lot of other significant targets. That kind of widespread havoc was certain to set the tone for this EO.

While some media stories suggest that the EO is a response to the Colonial Pipeline attack, I don’t believe it. A document of this size and depth couldn’t have been written over the weekend between that attack and the time the EO was released. Its scope is simply much further reaching and broader than the ransomware attack at the center of the Colonial Pipeline issue for that to be the case.

The goals of this major initiative to secure the software supply chain aren’t obvious on first reading of the EO, but the EO Fact Sheet proves helpful here. I’ve extracted four objectives from that document that stand out for me:

Goals of the Executive Order 14028:

- The Executive Order will improve the security of software by establishing baseline security standards for development of software sold to the government…

- …requiring developers to maintain greater visibility into their software and making security data publicly available.

- It stands up a concurrent public-private process to develop new and innovative approaches to secure software development and uses the power of Federal procurement to incentivize the market.

- …it creates a pilot program to create an “energy star” type of label so the government – and the public at large – can quickly determine whether software was developed securely.

How exactly does the order plan to achieve these objectives? Well that’s still unclear. What is clear is that Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) is a core concept with no fewer than 14 mentions. Two key directives related to SBOMs include:

4 (e) (vii) providing a purchaser a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) for each product directly or by publishing it on a public website;

4 (f) Within 60 days of the date of this order, the Secretary of Commerce, in coordination with the Assistant Secretary for Communications and Information and the Administrator of the National Telecommunications and Information Administration, shall publish minimum elements for an SBOM.

As a point of interest, the aDolus team has been actively involved with the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) SBOM Framing Committee in defining and testing these elements.

Sharing Your Information

After working through Section 4, I went back to pull apart Section 2: Removing Barriers to Sharing Threat Information. Again the EO Fact Sheet proved to be helpful, making the goal of Section 2 clear:

Removing any contractual barriers and requiring providers to share breach information that could impact Government networks…

There are 13 directives spread over the 3 pages in this section. They point to a single main objective: to make certain that all U.S. Government contracts require service providers to collect and share cyber event information with U.S. agencies.

Specifically, Section 2 calls for a review and update of the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) and Defense Federal Acquisitions Regulation Supplement (DFARS) to require that service providers:

- Collect and preserve information relevant to cybersecurity event prevention, detection, response, and investigation.

- Share the cyber information with the cybersecurity and investigative agencies.

- Share the cyber information using industry-recognized formats.

- Cooperate with Federal cybersecurity and investigative agencies involved in investigating incidents or potential incidents.

It’s interesting to note that the information sharing is 100% unidirectional (a data-diode anyone?) with the flow going from private industry to the government. There’s no mention of removing the barriers that prevent the government from sharing threat intelligence with operators of critical infrastructures. I find this unfortunate, having personally experienced situations when a little government threat-intel would have significantly improved a security team’s ability (and management’s motivation) to defend an OT system from cyber attack.

At first glance, I thought these changes to government contracts would impact only the IT companies that provide contract services to the federal government. However, I then I read the first line of this section again:

The Federal Government contracts with IT and OT service providers to conduct an array of day-to-day functions on Federal Information Systems.

It is not clear to me how an OT service provider might conduct functions on an IT system. Maybe this is simply a requirement to keep the electricity to the server room flowing. One thing is certain: OT companies are specifically called out — and I’m positive that was intentional.

Perhaps this reference to OT service providers is a result of the Colonial Pipeline incident. On Tuesday, May 11, four days after that attack started, the acting Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) Director, Brandon Wales, told the Senate Homeland Security Committee that CISA was still waiting for Colonial Pipeline to share key data about the attack. Colonial didn’t even contact CISA after discovering the hack, Wales said. Instead, the company contacted the FBI, which then brought in CISA. I’m just guessing, but it’s possible that a frustrated CISA leadership team added the “OT” reference to Section 2 that Tuesday afternoon.

Finally, while the stated goal is the sharing of incident data, some language in the section is considerably broader. Section 2(e) refers to the information necessary for the government “to respond to cyber threats, incidents, and risks.” This would include a wide range of security information and may implicate companies that sell cybersecurity data to the federal government. Companies in the OT threat intelligence business will need to watch this closely.

The Cloud is Now

While the Federal Government has been talking up cloud technologies for the past decade, its use of cloud technology has been uneven and its governance of cloud security has been immature. Section 3: Modernizing Federal Government Cybersecurity directs CISA to develop secure cloud adoption practices and guidelines, offer incident response services to government cloud users, and set policy on how agencies should work with partners like CISA and the FBI in responding to cloud incidents. It is clear that cloud technology is going to be a big area of attention in this administration. Companies with secure and robust cloud solutions will be the beneficiaries.

Section 3 also orders the government agencies to modernize its authorization and data protection strategies. Specifically, it sets a 180-day deadline for all Federal Civilian Executive Branch (FCEB) agencies to adopt multi-factor authentication and encryption for all data at rest and in transit. If you supply a product that doesn’t support multi-factor authentication, you (and your clients) will have a lot of explaining to do if it is used in government operations.

Timeline for Compliance

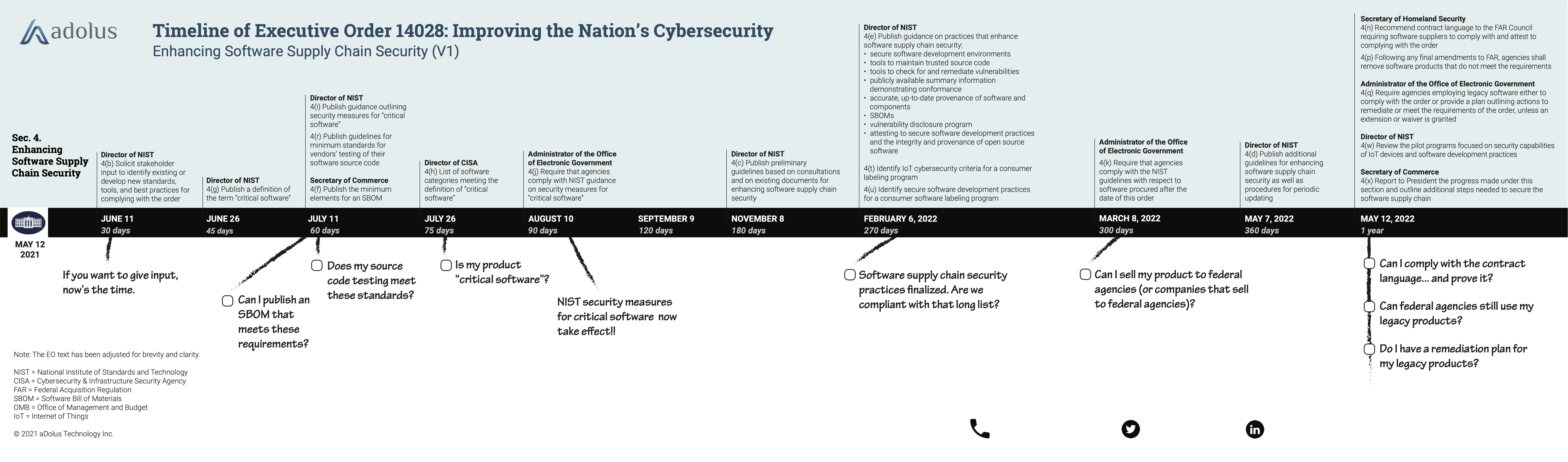

It takes a lot of digging to extract the exact schedule from the order, but the following timeline should help. It includes the due dates for the various supply chain directives, highlighting those that most impact software suppliers. Click the image below to be directed to more information on the timeline.

Executive Order 14028 – The Bottom Line

Executive Order 14028 – The Bottom Line

Suppliers of ICS/OT software products to the government (or suppliers to a company that supplies to the government) have some work to do. The software security information these companies are required to share with clients will change significantly in the next 365 days.

It is important to note that the new EO rules apply to “software procured after the date of this order.” Companies won’t have 6 or 12 months after the new rules are published to comply. Any software being sold today will need to follow the to-be-defined rules retroactively back to May 12, 2021.

The Executive Order doesn’t make it clear when service providers, be they IT or OT, have to comply with the new contracting agreements. However, based on previous FAR rule change cycles, we can assume that the period for public comments will close in late December 2021 and the FAR Final Rule will occur in late 2022. Contracts after that date will have to follow the new information sharing requirements.

This EO is going to impact the industry in a way that no other U.S. cyber legislation ever has. It will also ripple far beyond the U.S., especially in the Middle East, where sovereign oil companies are looking to duplicate these requirements for their OT Software Supply Chain. Even if your company does not sell to the U.S. Government, expect to feel the effects of this EO over the next few years.

About the author

Eric Byres is an ISA Fellow and internationally known expert on OT and IIoT cybersecurity. He and his team at aDolus Technology have been researching and creating SBOMs for the IIoT market since 2017. IIoT companies looking for guidance on creating SBOMs or enriching SBOM data — or on software supply chain security in general — can contact Eric at info@adolus.com.

Eric Byres is an ISA Fellow and internationally known expert on OT and IIoT cybersecurity. He and his team at aDolus Technology have been researching and creating SBOMs for the IIoT market since 2017. IIoT companies looking for guidance on creating SBOMs or enriching SBOM data — or on software supply chain security in general — can contact Eric at info@adolus.com.