Smart buildings – what’s the value to smart cities? Part One

Next generation technologies, such as the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), 5G, and data science, are poised to transform today’s cities into advanced smart cities. These cities are more resilient, safer, healthier, economically vibrant, and attractive to their residents, businesses and visitors. Despite these benefits, building a smart city is a complex multi-decade undertaking from the top-down. But an organic bottom-up approach is also necessary to complement the top-down efforts. A smart city is built one block, one park, one building, one neighborhood, one community at a time. Intelligent buildings are one critical component of a city’s transformation to become a smart city.

Smart buildings incorporate IoT and advanced digital technologies, algorithms and analytics, to bring new and significant value to tenants, building owners and operators. These benefits range from increased tenant productivity and safety, lower operating costs, and higher satisfaction. What value do cities get from smart buildings? Why should city officials and residents want smart buildings in their cities? Why should cities encourage the development and retrofitting of smart buildings?

While the benefits and Return on Investment (ROI) of smart buildings are well documented for tenants, building owners and operators, similar information for cities are limited at best. In addition, cities measure the benefits and ROI of smart buildings differently, and look beyond financial metrics. Part One of this two part article provides an understanding of the types of things that cities care about, and leads to a new set of metrics for evaluating the ROI of smart buildings. Part Two provides a framework for identifying how and where smart buildings provide value to the things that cities care about. These benefits vary from city to city, as each have different “care-abouts” and priorities. Part Two ends with a sample set of these benefits mapped into this framework. More about Smart City and Industrial IoT Applications

What do cities care about?

Cities are dynamic entities with diverse constituents and complex geographical, economic and political needs. In order to understand how cities benefit from smart buildings, we begin with some background and understanding of the drivers of civic value. We will start with the things that cities care about (civic outcomes), who creates these outcomes (outcome providers), and how the value for these outcomes is quantified and evaluated by city stakeholders. Ultimately, these interconnected outcomes must lead to the ultimate overall ROI for a city – a place that is healthy, productive, safe, self-sustaining and attractive over time, and where citizens and businesses choose to live and operate in.

City Outcomes

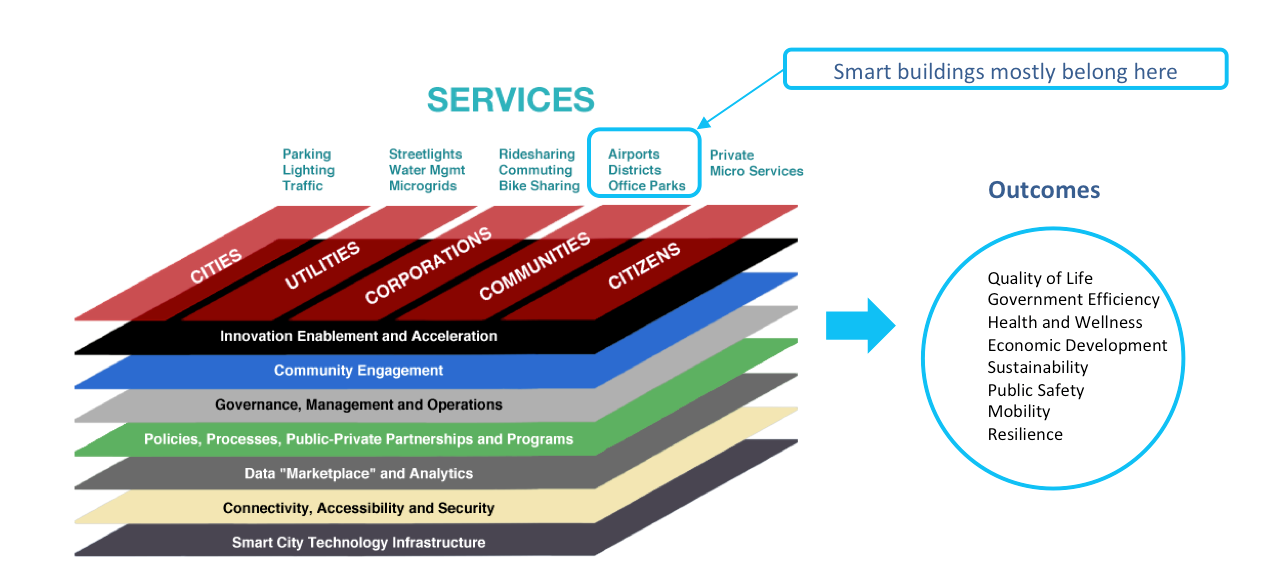

A city, large, medium or small, is in the “business” of creating and maintaining civic outcomes for its residents, businesses and visitors (Figure One). While all cities care about these outcomes to a certain extent, some outcomes are more relevant to them than others. Each city is unique, and its focus on specific civic outcomes reflect its unique economic, geographic and political priorities, and the needs of its many constituents. For example, economic development is a priority for some cities, while public safety and quality of life are more important for others. These outcomes are documented in a city’s strategic vision and plans, codified in its policies and regulations, and implemented in the form of funded initiatives and programs.

City outcomes are created by an ecosystem of “outcome providers”

Who creates these civic outcomes? City government is a creator of civic outcomes, but it is not the only one. Civic outcomes are created, delivered and maintained by an ecosystem of five groups of “outcome providers” – cities, utilities, corporations, communities and citizens (Figure Two).

Each “outcome provider” is responsible for delivering outcomes within its scope and domain. For example, the city is responsible for such things as maintaining streets, traffic signals and parks, while utility companies are responsible for gas, water and electricity. In other areas such as mobility, the city and private companies collaborate together to provide bus service, taxis and ridesharing, scooters, bicycles, and on-demand specialized transport services. This provider ecosystem works collaboratively to deliver certain outcomes in some cases, while working independently with limited to no collaboration in others.

Supporting these city “outcome providers” is an infrastructure comprised of people, organizations and businesses, policies, laws, processes and technology integrated together to create the desired outcomes. The responsive civic ecosystem is adaptive, agile and always relevant to all those who live, work in and visit the city. When advanced digital technologies, such as IoT, AI and analytics, are incorporated and integrated into this underlying infrastructure, new disruptive and transformational civic outcomes are created.

In the Strategy of Things civic ecosystem model, the smart building is an outcome provider to the city. In order to be relevant to the city, smart buildings must create those outcomes that cities care about, and to do it in ways not possible before, or with less cost, greater efficiency, and less resources.

City outcomes are measured differently

In business, ROI is a common metric used to determine whether a new initiative should be undertaken, how existing ones are performing, whether those should be continued, and what new resources should be applied. As a business has many competing initiatives and priorities, management allocates its limited resources to those that generate the highest returns, financial or otherwise. Except in strategic instances, business initiatives typically meet a minimum ROI threshold to be considered or to continue.

In contrast, cities are not businesses. Cities have different goals and “business models”. They do not create revenues to make a profit, but to create, maintain and enhance city services. Cities create services and often solve problems that have negative ROIs but serve a “common good”. They serve “customers” and stakeholders, as well as sectors and communities that businesses do not find profitable to service. Their main source of “revenues” is from taxes, as well service fees (parking, citations, administrative fees, etc.), designed to offset the cost of providing the various services.

Cities focus on creating city outcomes (Figure One). In addition to a ROI based solely on financials, cities also evaluate a ROI based on effectiveness of the delivered city outcomes. For example, cities evaluate for every investment dollar spent or resource applied:

- How many new jobs were created?

- How much crime was reduced?

- How many lives were saved due to a faster response time?

- How many homeless families have we taken off the streets?

- How effective were we in getting community participation on key issues?

The ultimate overall ROI for a city is that its initiatives and programs lead to a place that is healthy, productive, safe, self-sustaining and attractive over time, and where citizens and businesses choose to live and operate in.

City outcome ROIs fall into three categories

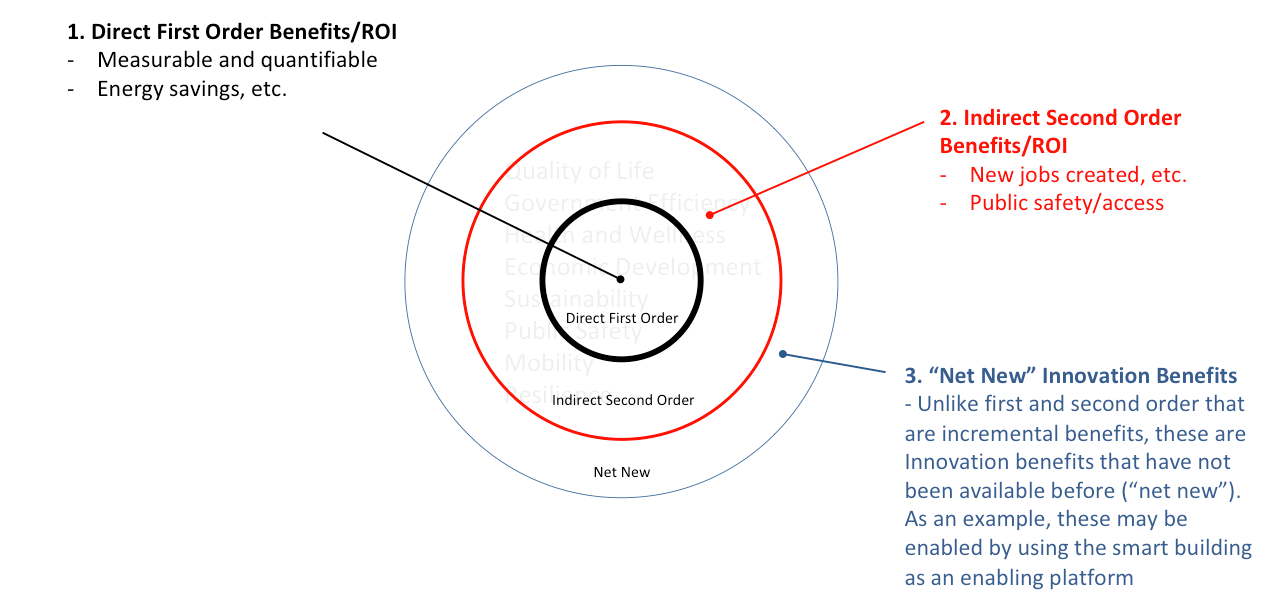

The benefits, or value provided, by city outcomes cannot always be easily quantified. The ROI for creating outcomes fall into three categories – direct benefits, indirect or second order benefits, and innovation benefits (Figure Three).

Direct benefits are those benefits that arise as a direct consequence of implementing a program or delivering a service in creating a civic outcome. For example, when a building transitions to a digital whole-building energy management system, the immediate benefit is a reduction in the energy consumed, and thus the savings in energy bills. Direct benefits are directly correlated to the initiative, and are typically easily quantifiable.

Indirect benefits are those that arise from a secondary consequence of implementing a program or delivering a service. For example, a smart building utilizes new and emerging digital technologies. These technologies create direct benefits such as lower energy costs, maintenance and operations management costs for the building owner. These smart building technologies require new skills and personnel to support it. Incorporating digital technologies will indirectly stimulate the local economy by creating the need for new jobs and a smart building business ecosystem to support and service the smart building. Depending on the specific benefit, indirect benefits are generally quantifiable (although not always as easily).

Innovation benefits are created from additional services that “piggyback” onto the newly implemented smart building infrastructure and capabilities to create new offerings. For example, the smart building makes its excess energy and communications capacity and capabilities available to the city. This excess capacity can be used as a smart city hub for hosting various communications and sensors for city use. These innovation benefits (and the services that create it) are not always known at the time the smart city is planned or constructed. These benefits fall into the “unknown unknowns” and are not easily quantifiable, nor do we always know when they will be “activated”. However, innovation benefits are real and must be specified (when known) and taken into consideration, even if it cannot be quantified. In a previous article we presented some of the highlights of smart city market growth.

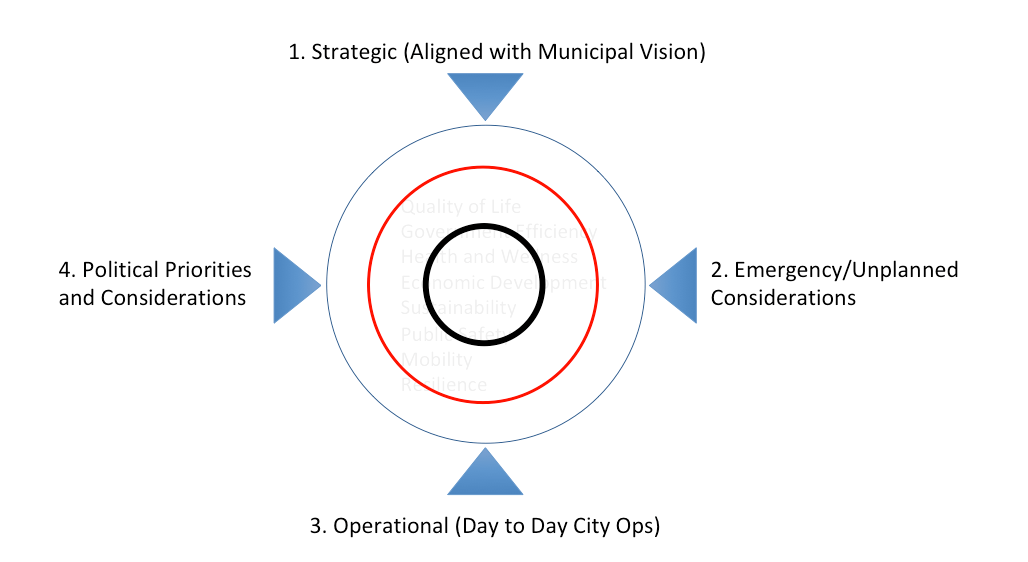

Civic outcome ROIs and benefits align to one of four civic dimensions

While smart buildings create tangible direct, indirect and innovation benefits and ROI for a city, how those benefits are valued varies from city to city. Each city is unique, and its focus on specific civic outcomes reflect its unique economic, geographic and political priorities, and the needs of its many constituents. Cities have a diverse set of stakeholders with differing perspectives and priorities. These stakeholders hold differing perspectives based on their roles, responsibilities, goals, and constituents. Figure Four shows the four dimensions that outcomes and benefits are reviewed against. There is no one single view of an outcome – different stakeholders within the municipal ecosystem will be looking at the outcomes from one of these perspectives.

The strategic dimension considers how the outcomes and benefits are aligned with a city’s long term vision and strategic needs. Many of these priorities are documented in a city’s general plan or vision document. These priorities are translated to specific initiatives which are implemented over the plan’s lifetime (typically 10 to 25 years).

The operational dimension considers how the outcomes and benefits are aligned with the day-to-day “run the city” activities and how well the city is able to provide services effectively and efficiently. These operational priorities vary from city to city, and are focused on resources, capabilities, costs, productivity and responsiveness. These priorities and needs are captured in each city department’s charter document and its operating plan.

The political dimension considers how the benefits are aligned with the long term and day-to-day electoral, governance and legislative needs of the city. It reflects the priorities of the political leaders and the citizens who elected them. These priorities may not always align with the city’s strategic and operational priorities. At other times, they may be consistent with the city’s strategic priorities, but not aligned on when they should be implemented. These priorities are typically documented in the campaign platform or promises that political leaders got elected on, and addresses the specific needs of their constituents.

The emergency or unplanned dimension considers how the benefits (also known as resilience dividends) are aligned with the resilience capabilities and resource needs of the city when something unexpected occurs. For example, a natural or man-made disaster, a massive event, or some other crisis event. These needs are captured in the city’s and department’s resilience planning documents.

When selling the value and ROI of smart buildings to municipalities, one must understand not only what direct, indirect, and innovation benefits are offered to the city, but also how these benefits are aligned to the four civic dimensions.

This article was written by Benson Chan, a Senior Partner at Strategy of Things, a transformation management consultancy helping companies innovate for a hyperconnected world. He has over 25 years of scaling innovative businesses and bringing innovations to market for Fortune 500 and start-up companies.

This article was written by Benson Chan, a Senior Partner at Strategy of Things, a transformation management consultancy helping companies innovate for a hyperconnected world. He has over 25 years of scaling innovative businesses and bringing innovations to market for Fortune 500 and start-up companies.